The Ego Does Not Need to be Eliminated

it's not your enemy, it's your bridge

My right eyeball twitches every time I read someone talk about the ego as if it’s something to fight, minimize, or eliminate all together and I need to say A Thing. (I do feel an obligation as a native of Baltimore to insert a joke here about the Key Bridge but maybe you can draw that analogy for yourself by the end of this article.)

Let me start by clarifying what I mean when I say “ego.” I think certain characters, like a certain former US president for example, may spring to mind, and we might label those characters “narcissistic.” This culturally refers to being egotistical, which is an inflated sense of oneself as morally superior. Ego has become equated with the quality of arrogance, which is maybe why it gets such a bad reputation. But this isn’t what the ego actually is.

The ego is not an enemy. The ego is a bridge. We build it, consciously or unconsciously. Either way, it’s there.

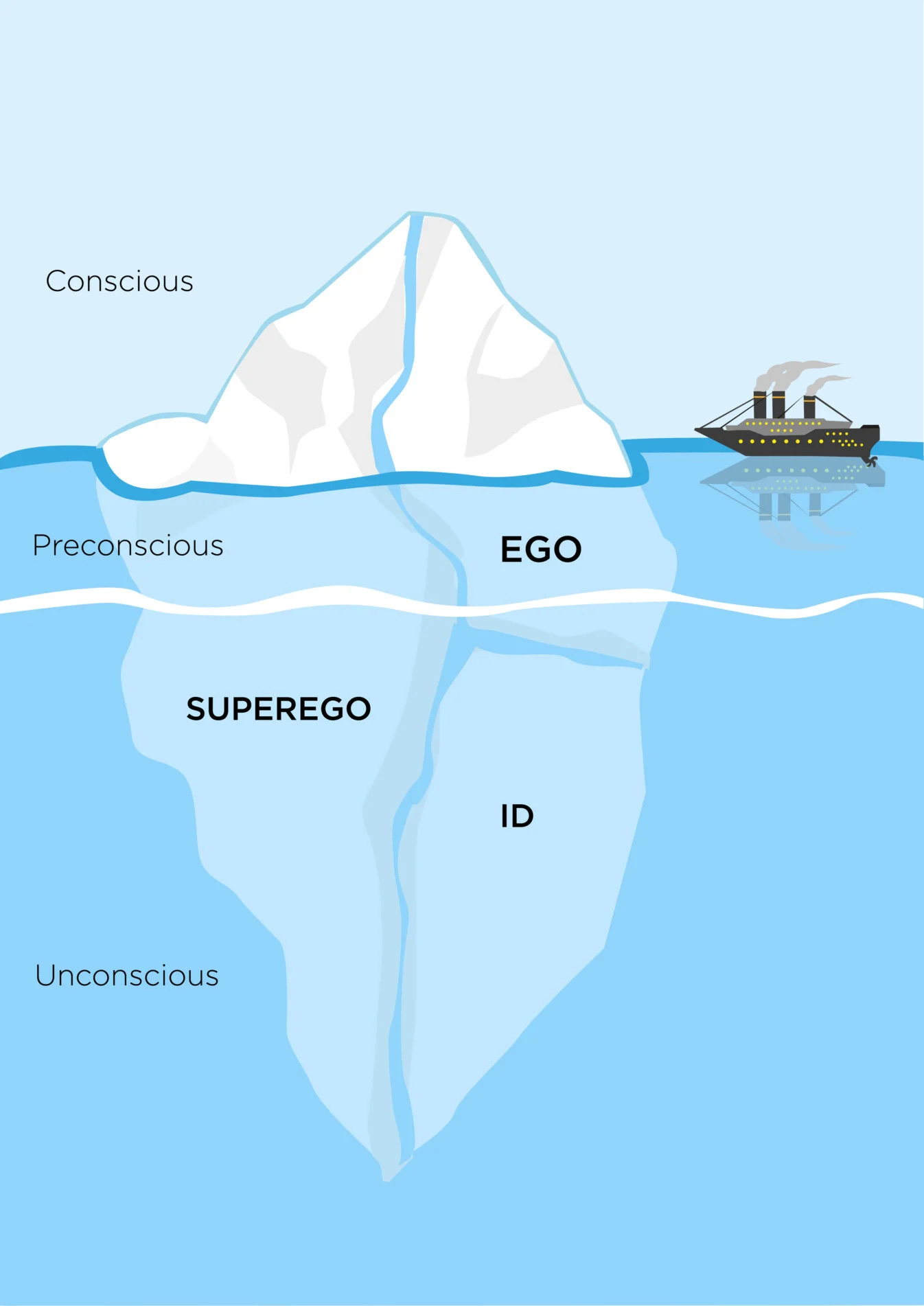

I studied some of Freud’s work in school and while I can hold space for how damaging many of his views on psychology were, I also hold space for how accurately he was able to reflect some of the Western mind back to us.

Elizabeth Lunbeck, a professor of the history of science, writes,

As Freud proposed in The Ego and the Id, three agencies of the mind jostle for supremacy: the ego strives for mastery over both id and superego, an ongoing and often fruitless task in the face of the id’s wild passions and demands for satisfaction, on the one hand, and the superego’s crushing, even authoritarian, demands for submission to its dictates, on the other. The work of psychoanalysis was “to strengthen the ego”; as Freud famously put it 10 years later, “where id was, there ego shall be.”

Essentially, Freud supposed that our primitive parts and our moral parts are in a constant battle for control over one’s psyche, and that a strong ego would be in control of both.

If you’re a spiritually- or emotionally-conscious person, these “agencies” may seem, well, a little dark and one-sided. Freud was certainly a product of his time (the patriarchy may never unhear “penis envy”), but he was also a Jew who survived interrogation by the Gestapo and died in exile after fleeing his home of Austria during World War II. He was no stranger to the ugliest acts of which a human is capable.

For Freud, the id represented the animalistic part of humans: our drives for pleasure (including but not limited to sex) and our drives for violence. He was under no illusion that anyone - anyone - could be pushed to violence, and that subscribing to a higher moral authority (the superego) did not excuse someone from their drives for violence. It was the ego’s job to mediate between the two.

Even New Agers do this. Spiritual bypassing is a thing we do when we can’t tolerate emotions that we’ve let someone code as “negative,” like anger, fear, doubt, worry, rage, or the urges for sex and violence. “Toxic positivity” is a dissociative response to these uncomfortable emotions, as though avoiding them will make them go away. We are taught to allow shame, the most poisonous of all possible emotions, to push these feelings down beneath the surface.

The source of that shame is often a sense of morality taught to us (directly or indirectly) by our families of origin, our religions, our school systems, and/or society (which includes media). Because shame is a social norm and is so deeply, unbearably painful, we’ll do just about anything to avoid feeling it. This, however, is not the same as morality, though it can look and feel like that.

When we try (consciously or unconsciously) to push all of these very real, very human things away, they don’t actually go away. They just get submerged and then they pop up somewhere else, like a balloon forced under water.

When we bring attention to these more challenging emotions and learn to tolerate the physical sensations that accompany them, we make them conscious. Once they’re conscious, we actually get to make intentional choices about what we do with them. When they’re being avoided, they do the choosing for us, often leaving us feeling helpless and even more ashamed.

This, I think, is the task of the ego. Not to mediate between primitive drives and morality, but to de-shame the drives and see that morality is not about which religion is right, but is about acting in all ways from a place of love. (Which does not negate outright the need for violence, because love can absolutely be violent, but that’s a story for another day.)

Which may sound simple at first glance. But, have you ever sat with your urge for violence? Have you sat with it long enough for it to turn into love? Or do you subscribe to the illusion that you are free from violent urges? Have you ever sat with your shame until it turned into love, or do you subscribe to the illusion that something about you makes you inherently unlovable?

This is the work of the ego. Not to avoid, but to learn to hold. Not to be hard and authoritarian, but to learn to be soft. We’re terrified of being soft with ourselves. We often genuinely believe that being soft with ourselves will make us weak, but being mean or shaming towards ourselves has never made us better. It’s never made it easier to love others. It’s never made it easier to change our behavior.

Softness and self-forgiveness is what changes behavior and releases shame. Allowing ourselves to gaze into the darkness of our very human nature and know that it won’t capsize us into destructive behaviors is the mark of a strong ego.

Some of you have parts right now saying to you, “Self-forgiveness will lead to arrogance.” It makes sense to think that, but it isn’t true. Narcissism and arrogance are avoidant behaviors: they are the unconscious mind dissociating from the perceived horrors of itself.

Avoiding the discomfort of accountability is not the same thing as forgiving oneself, though they can look similar.

Narcissistic traits result from a person being frozen at a very early stage of emotional development, before a real sense of self has developed. Because that sense of self is underdeveloped, it’s fragile, which is why people who struggle with narcissism, arrogance, and egoism lash out when they are criticized or told how their behavior has impacted another person. This is why they exhibit controlling behavior towards others. A person who struggles with narcissistic traits has an ego that knows the person is fragile, childlike, and incapable of the complexity of emotional nuance. The ego is compelled to protect, rather than reflect, because reflection will topple the person’s carefully constructed world.

This is why they insist upon their greatness, not because they actually believe they are great. A person who is confident in loving themselves can tolerate criticism without collapsing into shame and self-judgment.

When we are brave enough to look deeply within and face the “horrors” within—but without shame and self-judgement—we cannot come out with arrogance. When we build a sense of safety and use the ego to reflect rather than to protect, we can build a bridge between the things inside us that feel dark and the things inside us that feel bright. When we have the skills, we can walk back and forth between these parts without fear of ourselves.

Releasing shame and self-judgment opens us to loving ourselves and reinforces the bridge. Once we actively practice self-love, we feel spacious and clearer on where we want to send our attention and energy. There’s no need to run or hide from parts of ourselves when we receive criticism because we have already explored all the creepy, shadowy places. We know the terrain.

Audre Lorde said, “Nothing I accept about myself can be used against me to diminish me.”

That is the gift of the ego.